As advocates for animals and the environment, we’re constantly reading up on new studies, reports and white papers. The problem is, without a background in higher academia or science it can be difficult to break through the barrier of jargon to get to the facts.

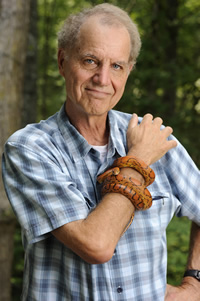

Dr. Harold Herzog, Professor of Psychology at Western Carolina University, popular blogger and best-selling author, said the problem is not with the layperson, but with the scientists.

Q: Why are scientific papers difficult to read for the general public?

A: That’s a really great question. I think there’s two reasons for it. One, which is pretty tough to get around, is that some of the scientific concepts have their own language. The average person is not going to know what an effect size is, or meta analysis. There’s not much you can do to get around that. The other reason, though, is that there’s a short hand in the scientific lingo that other scientists can understand and laymen can’t. Some scientists will intentionally obfuscate – make things sound more complicated than they are – because it makes the writer seem smarter.

Q: Is this something scientists are taught to do?

A: I think that’s absolutely true. I think, generally speaking, scientists and academics are trained in this stilted, arcane jargon and I don’t think it serves the sciences, or academia, very well. At some point, I decided I would try to avoid that; I would write my scientific papers so they’d be understandable by the laymen, and I think other scientists appreciate that.

It’s like the law: there’s a lot this arcane language in it. But there’s been a tendency to simplify it so an average person can understand a contract.

The American Psychological Association is emphasizing more than ever before the importance of clarity.

Q: What are some key points that general readers should be aware of when reading scientific papers?

A: If there’s a take home message, it’s this: what the average person doesn’t understand is that science is not really about facts; it’s not about the truth with a capital ‘T.’ It’s really a process. Usually, to say something is scientifically true doesn’t mean it’s absolutely true, it means you’re 95 per cent sure that something’s going on. That doesn’t apply to everyone and everything, though.

Even that is tentative. What one lab might find true in that 95 per cent sense another lab may find something completely different. What science journalists usually do is talk to more than one person. They’ll talk to the authors of a report and get their take on the findings; but then they’ll usually call someone else to get a different take on how another scientist sees it. Scientists disagree – the more important the idea, the more likely they are to disagree about it.

Q: What do you do when there are conflicting reports?

A: I say I don’t know the answer.

Q: Do scientists have biases?

A: Scientists are biased as hell. They’ll stake out some territory and it’s hard to get them to change their mind. They’ll do experiments that support their own theories. They tend to read other people who tend to support their own theories. And they tend to be more vigilant and critical. When you put on a lab coat, your biases don’t magically go away. That’s my experience.

Hal encourages those interested in reading studies to look for multiple sources, varying reviewers, similar (and opposing) studies and to consider the reputation of the publication in which the study was published. In his Psychology Today blog, Animals and Us, Hal regularly reviews current and new scientific literature.