“We started with a cookie jar of names,” said Bunty Clements, long-time director of The Fur-Bearers, prior to her passing in 2010. The beloved story of George and Bunty, partners in life and advocacy, is the origin many supporters of The Fur-Bearers know. Their successes in the late 1960s and early 70s propelled The Fur-Bearers (then The Fur-Bearer Defenders) into the national spotlight and paved a path still followed 50 years later.

But the beginning of The Fur-Bearers began not with George and Bunty, but in letters to the editor in pre-World War II Canada and a communal desire to do better for animals.

Letter Writers

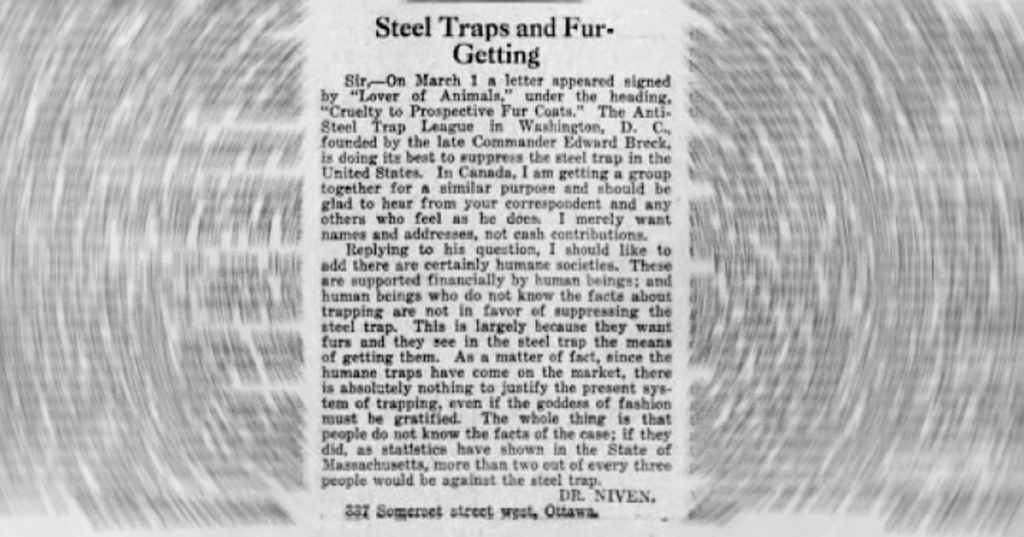

In the spring of 1931, a New Westminster man, Ernest Bacchus, wrote to the Vancouver Province, imploring a humane solution to the notorious steel leg-hold trap. Through incredible coincidence, Dr. Charles D. Niven in Ottawa saw the Bacchus letter and replied.

“On March 1 a letter appeared signed by ‘A Lover of Animals,’ under the heading, ‘Cruelty to Prospective Fur Coats.’

The Anti-Steel Trap League in Washington, D.C., founded by the late Commander Edward Breck is doing its best to suppress the steel trap in the United States. In Canada, I am getting a group together for a similar purpose and should be glad to hear from your correspondent and any others who feel as he does. I merely want names and addresses, not cash contributions.

Replying to his question, I should like to add there are certainly humane societies. These are supported financially by human beings; and human beings who do not know the facts about trapping are not in favor of suppressing the steel trap. This is largely because they want furs and they see in the steel trap the means of getting them.”

Vancouver Province, Sunday, April 12, 1931

Scan of original copy of the April 12, 1931 Vancouver Province.

This simple response in a Vancouver newspaper sparked a relationship between Bacchus and Niven; it was the beginnings of what would become the Canadian Association for the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals.

“Your short letter in the Vancouver Province … in respect to the matter of Steel Traps in the capture of Fur Bearing Animals was drawn to my attention by my daughter and the nature of this reply and other contents will explain and convey to you our feelings in respect to the same.

“In conclusion let us say that whilst we do not at present know just what your procedure may be in respect to the group you suggest trying to get together, you may have our assurance that anything we may be able to do that will in any way, shape, or form afford protection to the defenceless creatures in the wilds of this vast Dominion against the disgusting and barbarous warfare carried on against them will always be at your command.”

Letter from Bacchus to Niven, dated April 17, 1931.

Dr. Charles D. Niven was a young, noted physicist who had graduated with a PhD from the University of Toronto after emigrating from Aberdeen, Scotland. While his professional career was noted through various journals, the character of Charles Niven is virtually unknown. In fact, his colleagues at the NRC had no idea he had an interest in animals until his death, when they discovered he had left his estate to multiple welfare organizations. In 1967, Niven published a book in Britain titled ‘A History of the Humane Movement’ that examined the concepts of animal welfare into pre-Christian times. No personal journals or records in his name could be located.

A second letter penned by Bacchus in May 1931 indicated an update from Niven. It implied that Niven had the support of the Toronto Humane Society and a brief concept for a ‘humane fur store’ to help popularize alternatives.

May 13, 1931

… I am putting before you today as a suggestion only, for you to make use of any points that may in your better judgement appear good, and eliminate those which do not appeal to you. My ideas are for the foundation of an active and aggressive organization which shall eventually become Dominion wide and represent a power to be reckoned with by our Legislature (sp) both Federal and Provincial when the time and conditions are ripe for an appeal to them.

Letters between the duo continued for the following year, with Bacchus calling for the formation of an association, and Niven seeking solutions from others across the country. In their correspondence, Dr. Niven wrote of a Mrs. McKeen in Halifax, who penned letters opposing the use of fur, and a Miss Clara Van Steenwyk in Vancouver, who sought other practical solutions.

Concepts such as farmed fur and “humane” traps were explored by the group, who ultimately formed the Canadian Association for the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals. They used advertisements in newspapers and had exhibits at events like the Canadian National Exhibition.

In 1939, the name was changed to The Association for the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals, though the group was not formally incorporated at that time, and it was based in Ontario.

But in that fateful year, Germany invaded Poland, marking the beginning of World War II. Some advertisements and letters continued appearing from the advocates into 1941. As the war escalated, and the United States of America entered the global conflict, the media attention given to the fur issue decreased. It wasn’t until the 1950s, when new leaders emerged following the end of the war, that the Association was again active.

Photos accessed via Heritage Burnaby. 1956 photo by Charles Edgar Stride.

Enter Winch

Ernest Edward Winch, a bricklayer turned politician who emigrated to Canada from Essex in the late 19th century, who became a significant factor in the future of the Association. Though he dabbled with politics as a young man, it wasn’t until 1993 that Winch (with his son Harold) was elected to the Legislative Assembly for British Columbia. His first piece of legislation that made an impact on animals was to require better living conditions and significantly more space for captive animals at Vancouver’s Stanley Park Zoo. Around this time, MLA Winch began voicing dissatisfaction with trapping methods in the province. The spring-pole trap, not often used, was banned thanks to efforts by Winch.

In 1942, Winch met with Clara van Steenwyk, an SPCA member who had worked with Niven and Bacchus in the formation of the original Association. She also aided in the funding of Frank Conibear’s first attempt at a quick-kill trap. Sisters Nona and Gretchen Webster also joined this meeting of minds.

Not long after, in 1952, the Association that had formed under Niven changed its name to the Canadian Association for Humane Trapping. The western group, with van Steenyk, the Webster sisters, and Winch, went in a different direction: on January 21, 1953, The Association for the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals was formed. On February 7, 1953, the Association was incorporated. There were eight members and $10 in the treasury.

George and Bunty

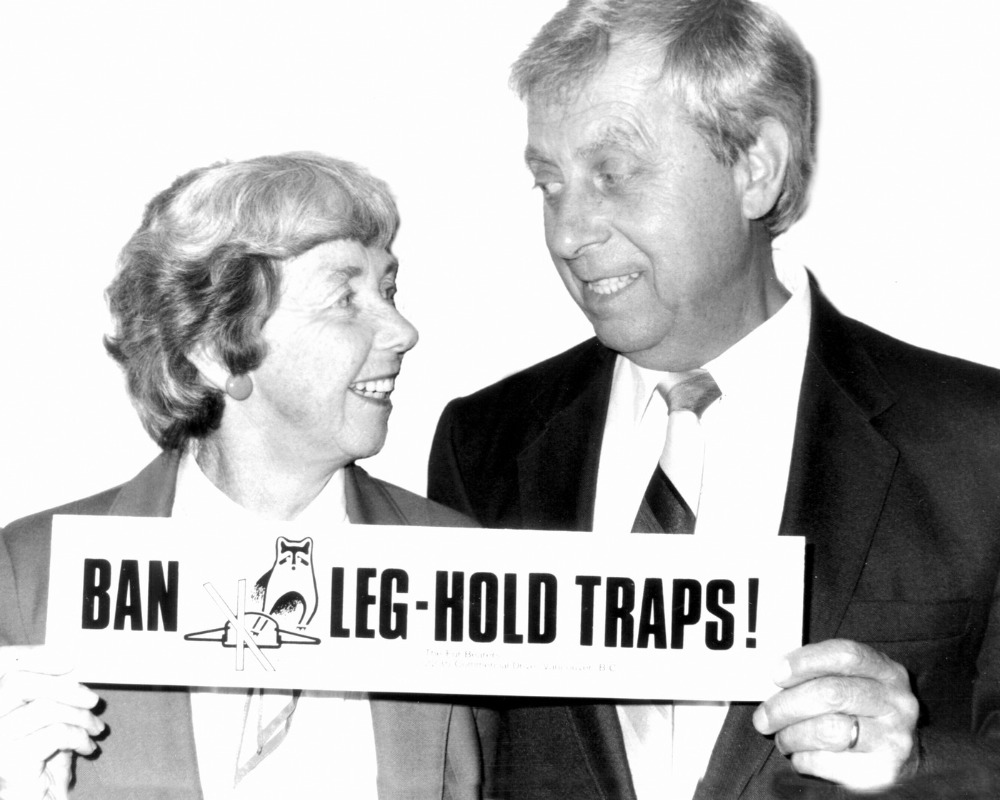

In the late 1960s, George Clement, a war veteran, was a school principal in Prince George, British Columbia, his wife Bunty a teacher. The couple was enjoying a stroll behind the school one day when it happened: George took a step and heard a click.

George instantly froze. He had been to war. He knew that sound. And death and destruction often followed. Fortunately, Bunty had not been to war, and was able to identify a large steel trap, not a mine, had latched onto George’s boot. Uninjured, but deeply unnerved, the pair found several more traps behind the school – where children sometimes played – and destroyed them. While seeking out the traps, they also stumbled upon a muskrat, exhausted and unable to free themself of a leg-hold trap.

In one written account, Bunty noted that after the muskrat had been set free “he was about 10 feet away from me when he suddenly turned and stared directly into my eyes…we understood each other. The little animal seemed to be saying ‘thank you.’”

Over the coming weeks, months and years, the power couple focused their education backgrounds on themselves: they became self-schooled experts in the world of trapping. They continued with their careers but never shook the feeling that something more could be done.

Tears were shed on more than one occasion by Bunty, who had said “I cried with the horrendous brutality of it all, but also decided that crying wouldn’t help. I should do something about it.”

As they readied for retirement, George and Bunty began volunteering their time with a little-known organization that focused on such issues. By the early 1970s, the organization had seemingly passed its hay-days; little structure was in place and action was a distant memory.

In 1973, Bunty became president and with nothing more than names in a cookie tin, drive and desire, a new age of the Association began.

Putting a Spotlight on Trapping

Through their respective times as directors and leaders for the Association, George and Bunty saw great success. They worked with film and television stars like Bruno Gerussi, Loreetta Swit, and a young Dr. David Suzuki, to produce short trapping videos that aired nationally on CBC.

George travelled to address the World Society for the Protection of Animals in Luxembourg, and the European Parliament. Though his appeals were strong, and garnered much support, the Canadian government began a significant pushback on proposed policy that would prohibit the importation of furs obtained through leg-hold and other traps in Europe.

As a result, The Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards was signed by Canada in 1997. This document, which does not define the word humane, was put in place to continue the trade of fur items from Canada to European nations.

At home, the Fur-Bearer Defenders focused on educating the public, and began seeking solutions to common issues relating to trapping – such as beaver dams. Beavers build dams when they hear running water – it’s an instinctual drive. This can create disruptions in human-built infrastructure by altering the flow of water. But, as demonstrated by innovators like Mike Callahan and Skip Lisle, managing beaver activities can be done humanely, without removing beavers, by using flow devices and other methods.

The Clements led the Association through the loss of charitable status, showed that a focus on solutions is effective, and that community and communication are paramount for change.

The end for George and Bunty came in a story both familiar and sorrowful.

On March 20, 2010, Bunty passed away.

Her fight to protect the fur-bearing animals of Canada – and the world – had come to an end, more than 40 years after it began.

At the age of 84, only three months after Bunty’s death, George passed on as well.

“They were such nice people,” recalled Anne Carchesio, an Association member and Director since the late 1970s. “They always saw the best in others and brought out the good in people. They treated people well, were honourable and kind. I think in many ways they were ahead of their time.

“George and Bunty were both teachers, they were communicators,” she said. “They understood the importance of knowledge and the importance of communicating with people in a way they’d understand. They’d show people the negative things, but also the positive. They knew how to help people feel that they could make a difference, to feel hope. You can’t save the world today, but you can save one life. I think they really knew that.”

Still image compliments Arise Productions

Present Day

Seventy years after pen went to paper and The Association for the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals was formed, the organization is stronger than ever.

A team of compassionate, skilled, and driven individuals keep issues related to trapping and fur farming in the news. Communities facing negative encounters with wildlife rely on The Fur-Bearers to provide focused educational support; government agencies are held to account when they kill wildlife; stories of wildlife and opportunities to protect and coexist with them are kept in the media spotlight; and, long-term, sustainable solutions are championed.

The Fur-Bearers, including our staff, volunteer board of directors, volunteers, and supporters past and present, are here today because of generations of people who knew that the lives of wildlife can be made better, and that solutions to end cruel practices exist. Every success we have for communities and the animals can be directly linked back to a letter in the Vancouver Province nearly 100 years ago. And every day we’ve stood up and spoken up on behalf of animals, we’ve done so with your support.

Thank you.

Donate Now!

The Fur-Bearers continue to rely on donations from supporters and animal lovers like you. Donations are eligible for a Canadian charitable tax receipt. Use the form below to make an online, secure donation now!