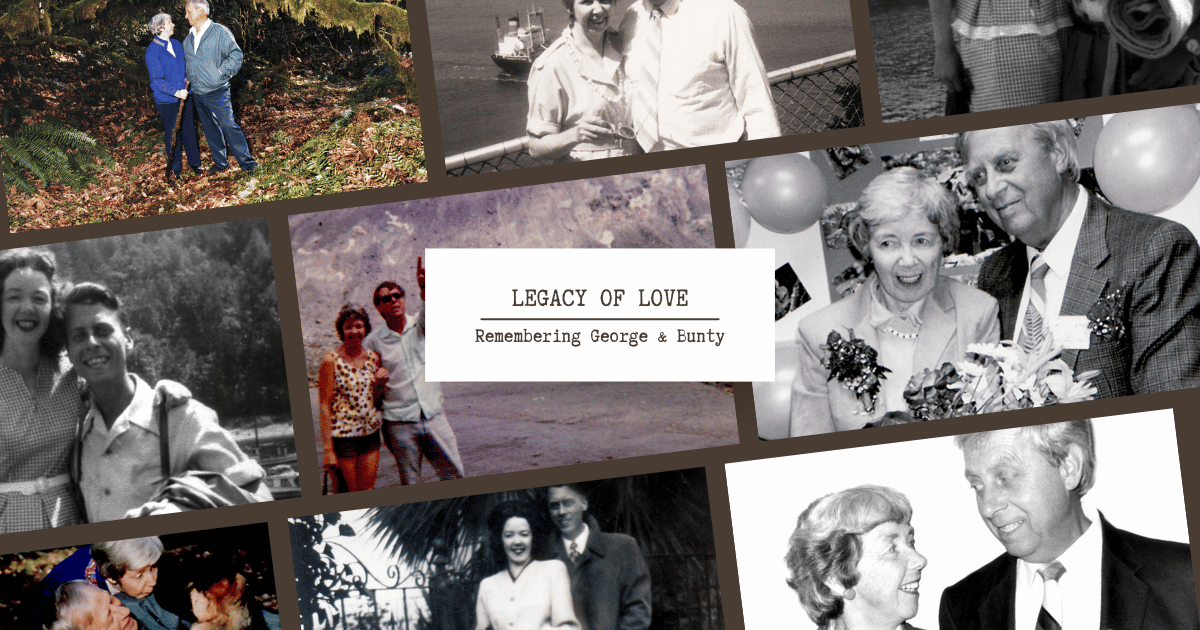

In the year of our 70th anniversary, The Fur-Bearers are looking back at some of the incredible accomplishments and people who have made an impact on the organization and wildlife in Canada.

Click here to donate to our 70th Anniversary campaign.

Two such people are George and Bunty Clements, who joined the organization in the late 1960s. Their 58-year love story is intertwined with The Fur-Bearers, and we wouldn’t be where we are today without the couple.

A Walk To Remember

Click.

The sound stops the heart of any war veteran. A single step, a soft footfall, and then the click. In wars of the past, that click was the last sound a soldier heard before the land mine beneath took his life.

George Clement was such a war veteran.

In the late 1960s, Clement was a school principal in British Columbia, his wife Bunty a teacher. The couple was enjoying a stroll in a forest behind their school one afternoon when it happened.

Click.

George froze. His palms became slick with sweat, his face drained of colour. He had heard that sound in the war. Death and destruction always followed.

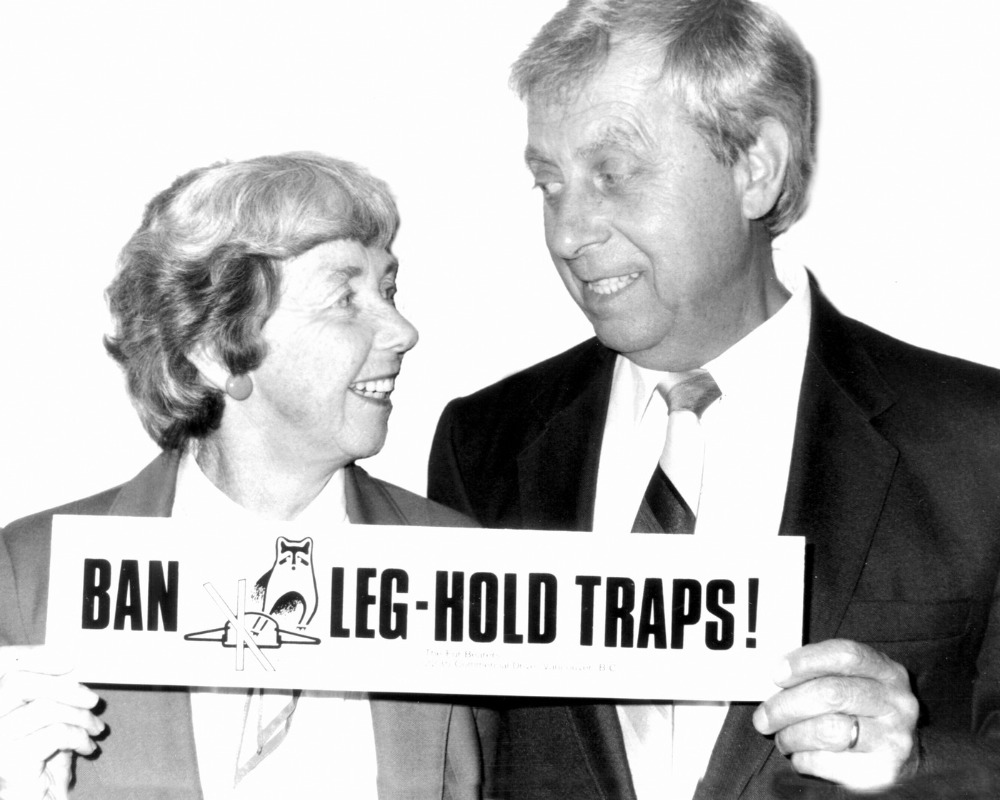

Bunty, however, had not been to war. The click was a surprise, but not a nightmare. She looked down and saw George’s boot caught in some kind of trap. A steel-jawed leg-hold trap, specifically.

The heavy material of his boot had prevented the deadly teeth from digging into George’s flesh. But he remained trapped by the device. Using a stick and their combined strength, George was able to get free.

The couple was astounded. It was clearly a trap left to capture, if not kill, wildlife. Less than 100 yards away was their school, where children played every day. George had been lucky. A small child might not be.

George and Bunty spent the rest of their afternoon searching the area and, as they found them, disarming the traps. It was their first exposure to the pleasure of knowing they had saved the lives of innocent animals. It was also their first exposure to the potential consequences.

As they were leaving, taking the winding path toward home, a disturbance in the pond caught the couple’s attention. Bunty rushed to the aid of a struggling animal, thrashing in the water. It was a small muskrat, half-drowned and unable to free itself of a leg-hold trap. In one written account, Bunty noted that after the muskrat had been set free “he was about 10 feet away from me when he suddenly turned and stared directly into my eyes…we understood each other. The little animal seemed to be saying ‘thank you.’”

The trapper who had staked the area approached. A long gun was levelled at George’s abdomen. A warning was given and George and Bunty eventually were charged with disturbing a legal trap line.

Over the coming weeks, months and years, the power couple focused their education backgrounds on themselves: they became self-schooled experts in the world of trapping. They continued with their careers but never shook the feeling that something more could be done.

Tears were shed on more than one occasion by Bunty, who had said “I cried with the horrendous brutality of it all, but also decided that crying wouldn’t help. I should do something about it.”

Upon their respective retirements, George and Bunty started volunteering full-time with a small B.C.-based organization, The Association for the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals. In the early 1970s, the group had seemingly passed their hay-day; little structure was in place and action was more a distant memory.

In 1973, Bunty became president and with nothing more than 300 names in a cookie tin, drive and desire, a new age of Association began.

Growing Up

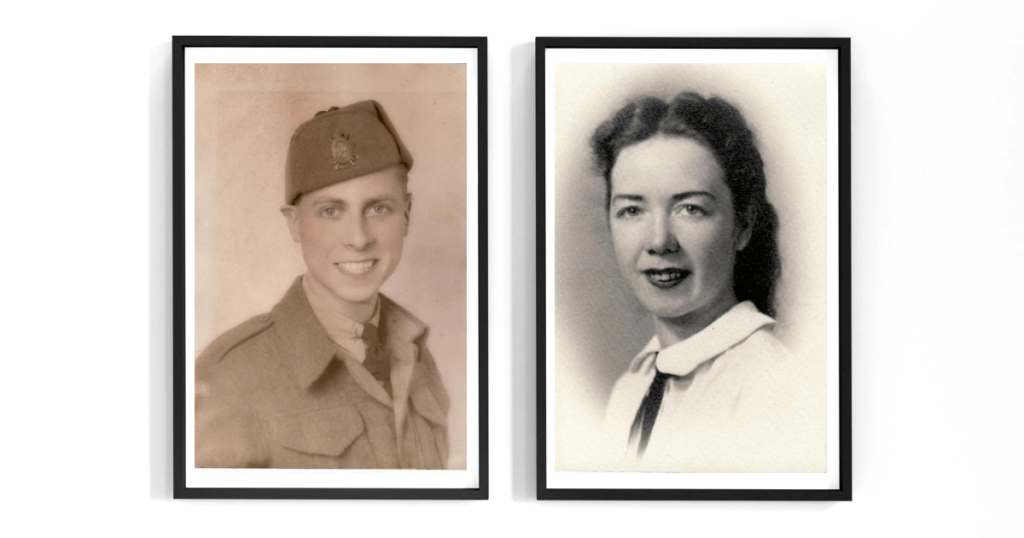

Both Bunty and George grew up as depression-era children in the poor homes surrounding Vancouver. Work was scarce for those capable of a trade and young boys and girls quickly became men and women as the fight for familial survival was being waged.

George, a bright boy and solid student, began working when he was 12, part-time during the week and full-time on the weekends. His family were welfare recipients and he – like many children of the day – was terribly ashamed of it.

“The social workers at the welfare office put so much pressure on me to quit school, which I loved and at which I excelled, so that I could work full-time to support our family,” George wrote in a short biography. “I was in grade 12 and still only 16-years-old when most students in this grade were older. Despite my pleas and desires to complete grade 12, I had to go to work – washing dishes on a ship.”

It was not long after George had taken on this employ that World War II broke out: the ship was commissioned into the Merchant Navy, painted with camouflage and a large 4-inch cannon was mounted on its stern.

Two years into his service with the Merchant Navy, George enlisted in the Canadian Armed Forces and was sent to Europe. The campaign was winding down and, after a brief stint in combat, George volunteered himself to fight in the Pacific against the Japanese. During his special training in the United States, the Japanese surrendered and he was thrust back into civilian life.

Though he had spent time as a full-time worker, seaman and soldier, George immediately dove into his education. Using army credits he was able to complete grade 12 and his first two years of university. Continuing to work full-time while attending school, George eventually earned his Bachelor’s Degree in Education and become a teacher, which ultimately led to his role as a school principal.

Bunty, meanwhile, was growing up in another depression-era home. Cardboard patched holes in shoes were common and rent money was often late. Much like George, Bunty worked through her final years of school and graduated as a teacher from a Vancouver school.

Teaching all subjects to a class of 40 students was boring Bunty, an enthusiastic and adventurous young woman. She learned of a Creative Dance for Children program being taught at some local schools and headed south to California.

In San Francisco she learned the basics and graduated with a teaching degree specializing in dance. When she returned to Vancouver to teach, she met George, who was still in university.

The couple moved together to a one-room school, 50 miles north of Prince George, where they taught (and George administered) students, a shared passion. They lived full and happy lives, they thought, until that fateful spring afternoon.

The Bittersweet End

The end came in a story both familiar and sorrowful.

On March 20, 2010, Bunty passed away.

Her fight to protect the fur-bearing animals of Canada – and the world – had come to an end, more than 40 years after it began.

At the age of 84, only three months after Bunty’s death, George passed on as well.

The cliché, dying of a broken heart, immediately springs to mind. The two were lovers, best friends and partners for 58 years. Between them, untold millions of lives were saved. Public knowledge of the torturous leg-hold trap may never have reached its climax had fate not intertwined the hearts of Bunty and George.

“They were such nice people,” recalled Anne Carchesio, an Association member and Director since the late 1970s. “They always saw the best in others and brought out the good in people. They treated people well, were honourable and kind. I think in many ways they were ahead of their time.

“George and Bunty were both teachers, they were communicators,” she said. “They understood the importance of knowledge and the importance of communicating with people in a way they’d understand. They’d show people the negative things, but also the positive. They knew how to help people feel that they could make a difference, to feel hope. You can’t save the world today, but you can save one life. I think they really knew that.”

The deaths of George and Bunty, who in their final years floated between retirement, volunteerism and leadership of the Association, did not stop Carchesio – or others – from continuing in their path. The path, often filled with pain and loss, was shown to them by the Clements.

“If we don’t keep going, who’s going to help these animals,” Carchesio asked. “Sure, I feel pain. But heavens, my pain is empathy – I’m not the one with my leg in a trap. I’m not the one who’s hurt. Sure, it’s not easy. But it’s a lot worse for the animals than it is for me. If I don’t keep on – if the Association doesn’t keep on – who’s going to help them?”

George’s death may have quickly followed that of his beloved wife. But it was not death of a broken heart. It was a race to see her once again.

You can help The Fur-Bearers protect wildlife for another 70 years by donating today. Donations are eligible for Canadian charitable tax receipts. Become a Defender by donating $5 per month and help The Fur-Bearers develop sustainable, solution-focused programs!